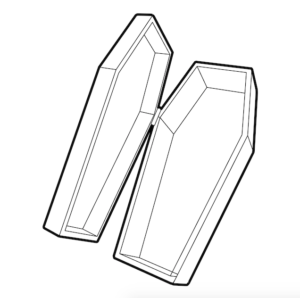

What’s the difference between a coffin and a casket? It’s a question I’d never entertained before working at Newman Brothers Coffin Works, but that’s the question we pose to all our visitors on our guided tours. Although the answer seems very obvious to me, nine times out of ten when I ask a group, I’m met with vacant or pondering looks.

The answer is in fact to do with the shape, but because the terms ‘coffin’ and ‘casket’ are used interchangeably, you’d be forgiven for never considering the differences, but here’s the main one: a coffin has six sides and is hexagonal, and a casket has four sides and is rectangular. Most of the time anyway. But it’s not the shape for shape’s sake that makes this subject matter so fascinating.

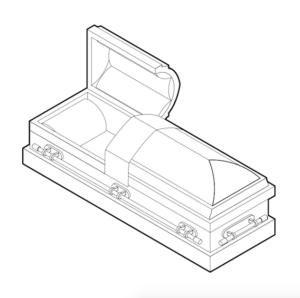

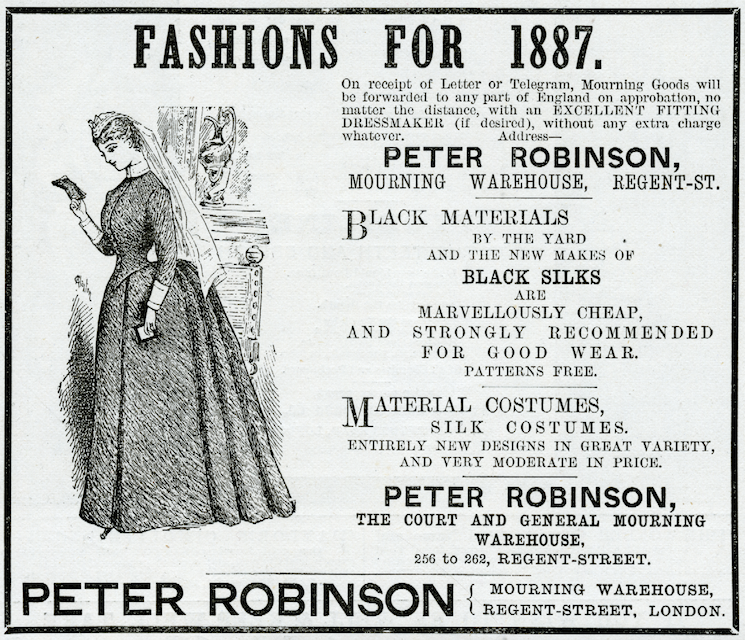

As well as making handles for coffins, Newman Brothers also made casket handles and casket-bar handles (see image above), as there’s a market for all styles in the UK, at least since the 1950s. However, Americans favour the casket, as the coffin died out in the States many years ago. But it’s the evolution of the casket as a direct descendant of the coffin that makes for an interesting study. This evolution is deep-rooted in socio-economic movements and to understand those changes we need to visit 19th-century America.

The ‘New’ World

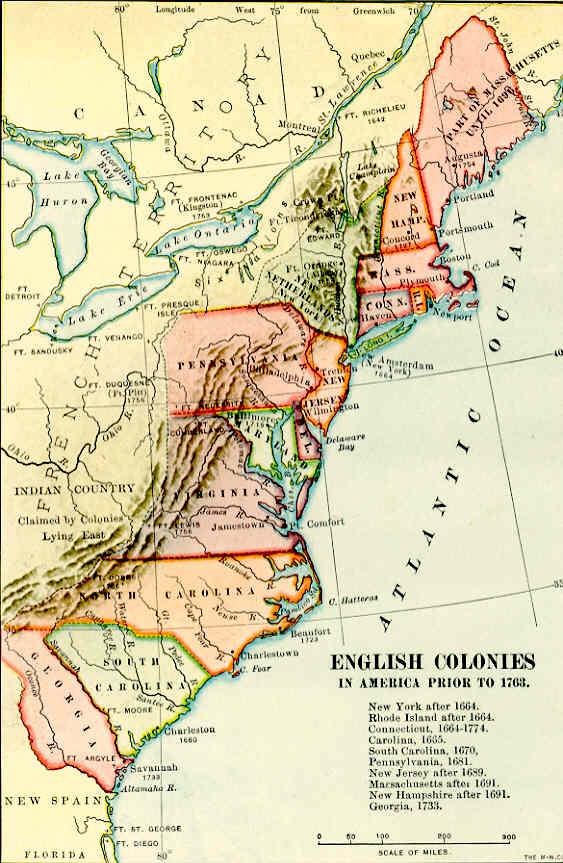

In 1700, a change in English law allowed all people to be buried in a coffin. Previous to this, coffins were for the most part reserved for the wealthiest in society and the poorest people were commonly buried in a shroud or winding sheet, and placed straight into the ground. The only type of coffin they would have encountered at this time was the ‘parish coffin’, a vessel used to transport the deceased from the church to the graveside in assumed dignity. The British American Colonies were no different and with the new law, by 1704 the use of coffins in colonial Maryland, for example, was at an all-time high of 90%. English mourning rituals had taken firm root in Colonial America, and the coffin was a key part of that ritual.

The Coffin

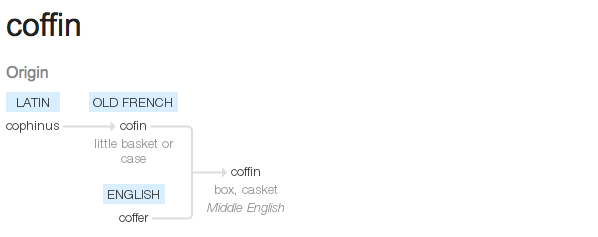

‘Coffin’ comes from the Old French word ‘cofin’, meaning a little basket, and in Middle English, could refer to a chest, casket or even a pie. A coffin at this point (by 1700) was predominantly hexagonal, with its traditional six sides, tapered at the shoulders, and at the feet. The tapered top half of the coffin was tailored to perfectly accommodate the width of a person’s shoulders, and it’s this anthropometric shape, which refers to the measurements and proportions of the human body, that proved problematic for some people.

Although four-sided coffins did exist in Britain, by the 18th century it was the standardisation of the English funeral that meant that hexagonal coffins dominated. Moreover, the term ‘coffin’ was universally used regardless of the number of sides the vessel possessed. The term ‘casket’ was not yet in common use.

The Casket takes shape

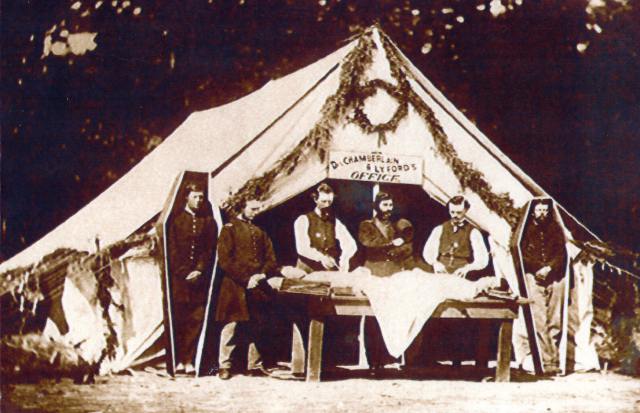

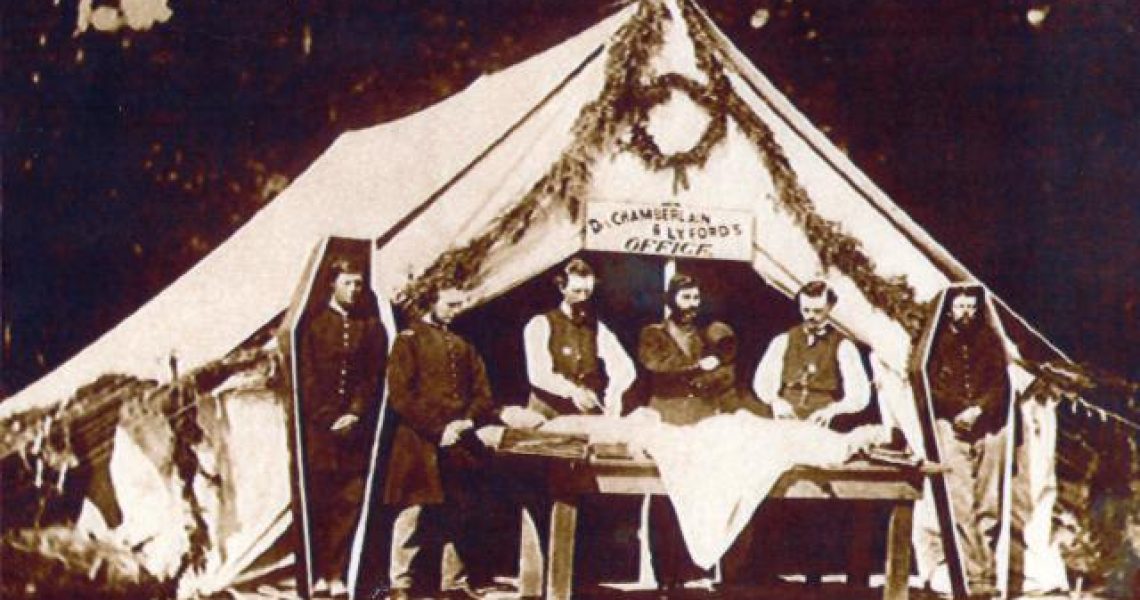

Hexagonal coffins had largely been in use in the North American Colonies in great numbers from 1700 until at least the middle of the 19th century, so what prompted their abandonment? There are a few theories. Although rectangular coffins were gaining in popularity before the American Civil War of 1861-1865, it was that war that firmly transplanted the design. In America, coffins were traditionally very plain and almost exclusively made from wood. Unlike in Britain, the coffin furniture trade in America was still in its infancy, and it was the Civil War that sparked a revolution in American funerary practices.

It was the violence combined with the scale of death that led to the ‘the beautification of death’ in America during this period, and it was the shift in both name and shape of the coffin that was an effort to distance the living from the unpleasantness of death, and the hexagonal coffins were part of that distancing. Many early American caskets were still six-sided, but noticeably grander. They also didn’t seem to taper at the bottom, as illustrated below.

It’s almost as if the coffin was too honest, too basic and unrefined. The change in name from coffin to casket reinforces this point, as ‘casket’ calls to mind a vessel for storing precious goods, a euphemism, yes, but seemingly also a mark of intended respect. For Americans, the idea of a casket seemed a more appropriate term to honour their dead.

At the same time, the post–revolutionary period saw traditional British customs of public mourning slowly wane and develop into something distinctly American. There was a new confidence in the air. Americans were now encouraged to buy local fabrics for mourning outfits, rather than expensive imported fabrics. This inward focus rather than a desire to imitate traditions from across the sea was arguably the beginning of America developing its own unique relationship with death, albeit one that had grown out of English traditions. But nevertheless there was a change in tide, a change that impacted upon the coffin. After making its pilgrimage across the Atlantic with the first English settlers, in less than just 150 years, the coffin was soon abandoned as a relic of the past, incompatible with this ‘new’ country and its burgeoning ideas of death, and therefore life.

By the turn of the 20th-century, caskets had all but replaced coffins in America. The casket can in many ways be seen as the American response to ‘refurbishing’ or improving the coffin; a new polished and upgraded model that dispelled centuries of deep-rooted meaning.

Sarah Hayes, Museum Manager

7 Responses

This is fantastic. What you did fir the dead defining how new world American you were. Great read

Thanks Tina!

Thanks Great

Superb piece, Sarah. During my childhood I saw the funerals of John F Kennedy and Sir Winston Churchill on television. It didn’t take long for me to realise that what Kennedy was buried in was rectangular and different to what Churchill had. I soon learned that the Americans used the word “Casket” to name their medium.

From the point of a child’s ignorance, I made an assumption that the Americans did not want a “shape of death”. After all these years, your piece (thanks to Josie for referring me to it) has confirmed this for me.

Thanks.

I’m 87 years old and still learning .

My grandpa said at 105 years old that he tried to learn something everyday. Though not rich by any means he was a very intelligent and interesting man. He was 75 when I was born and would walk 4 miles holding my hand telling me stories of his life until he was 94. Wish I knew then that I wouldn’t always have my best friend.

Loved this report!!

Great