Since we opened the museum nearly ten years ago, the mystery of Edwin Newman has flummoxed us. Frustratingly we’ve never been able to determine why after setting up the Fleet Works with his brother, Alfred, just one year later the partnership was dissolved.

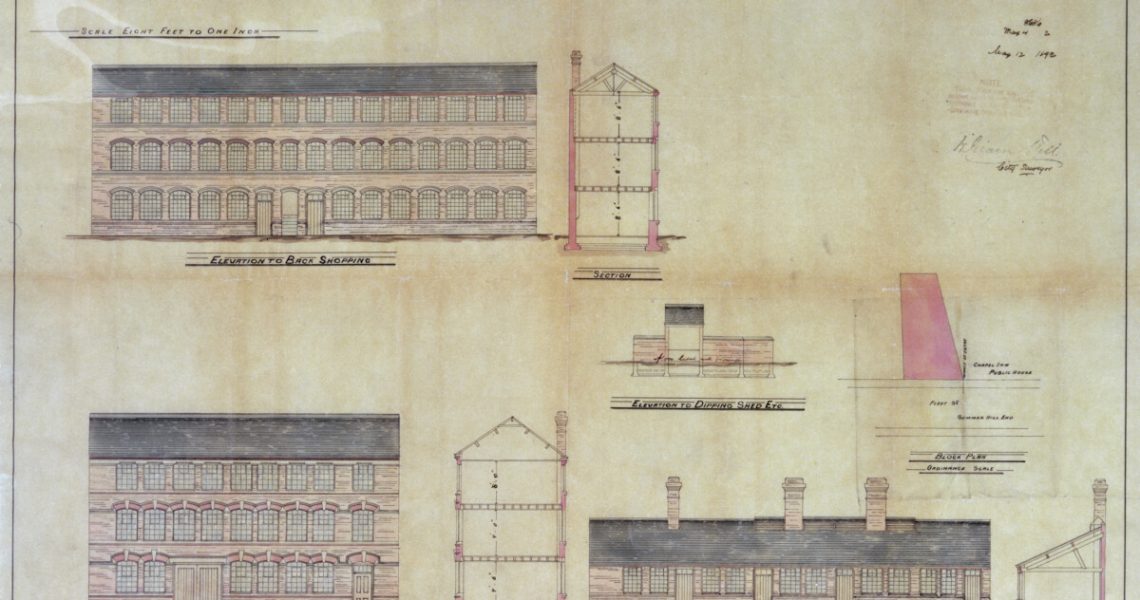

The Fleet Works, otherwise known as Newman Brothers Coffin Furniture Works, was established on Fleet Street in 1894. Edwin and his brother Alfred had been in business together long before this, originally setting up as brass founders in 1882. They specialised in brass cabinet fittings and were based on Nova Scotia Street.

Business seemed to be good and they commissioned a state of the art coffin furniture manufactory in 1892. A sensible business decision it would seem: after all they made this decision during a period when people were spending unprecedented amounts on funerals, much more so than on cabinet fittings. And as we always say, if you could make a handle for a cabinet, you could make one for a coffin, as the manufacturing process was eaxctly the same.

So, why then did Edwin leave? Well, until very recently we really didn’t have any idea, which just left space for conjecture, but now we can at least back some of that guess work up with concrete facts.

Edwin, the older of the brothers by five years, dissolved his partnership with Alfred in 1895, just one year after moving to Fleet Street. This is the part that has always intrigued us. Commissioning a purpose-built manufactory wasn’t cheap, so why leave after just one year? It would appear something significant happened between the two brothers. Money troubles or a family rift maybe?

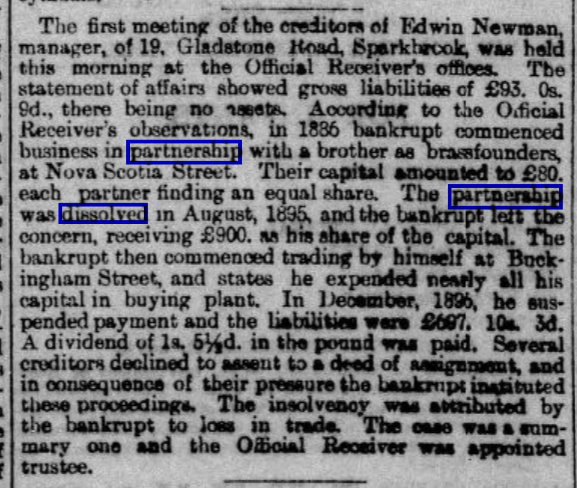

Fast forward to 1898 and some research into various newspaper archives. From the Birmingham Daily Gazette dated 20th July 1898, we learned of a bankruptcy hearing for Mr Edwin Newman.

Notice was given that “Edwin Newman of Gladstone Road, Sparkbrook, Manager”, was due to appear at a First Meeting on 27th July 1898 at 174 Corporation Street and thereafter on the 3rd August 1898 for a Public Examination at County Court.

With this information we then discovered a report relating to the ‘First Bankruptcy Meeting’ of creditors of Edwin, which was reported in the Birmingham Daily Mail on 27th July 1898.

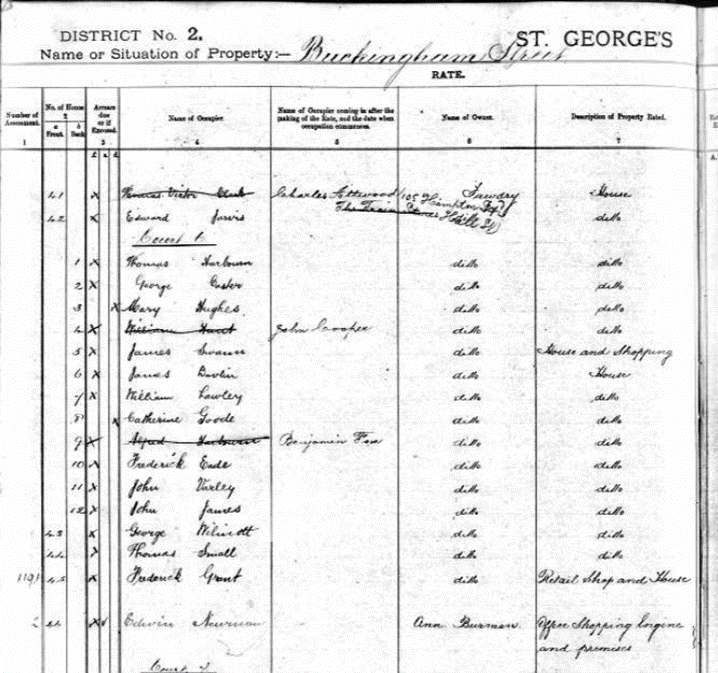

From that we can see that shortly after dissolving the partnership with Alfred in 1895, Edwin received £900 in capital from his share at Newman Brothers and then invested nearly all of it into buying plant for another business, commencing trading by himself at Buckingham Street. This document doesn’t actually say what type of business he set up or any specifics about the ‘plant’. For that piece of information, we needed to next consult the Birmingham Rate Books, which give us a bit more information about the type of manufacturing Edwin was carrying out at his rented premises on Buckingham Street.

From this, there is a description of “office, shopping, engine and premises”. This would appear to be an almost identical description of the Newman Brothers’ Fleet Street set up. Could Edwin have opened a like-for-like business? Or did he return to manufacturing cabinet fittings, or perhaps he entered into an entirely new manufacturing area? The Rate Book doesn’t tell us that unfortunately, but we knew a document that would.

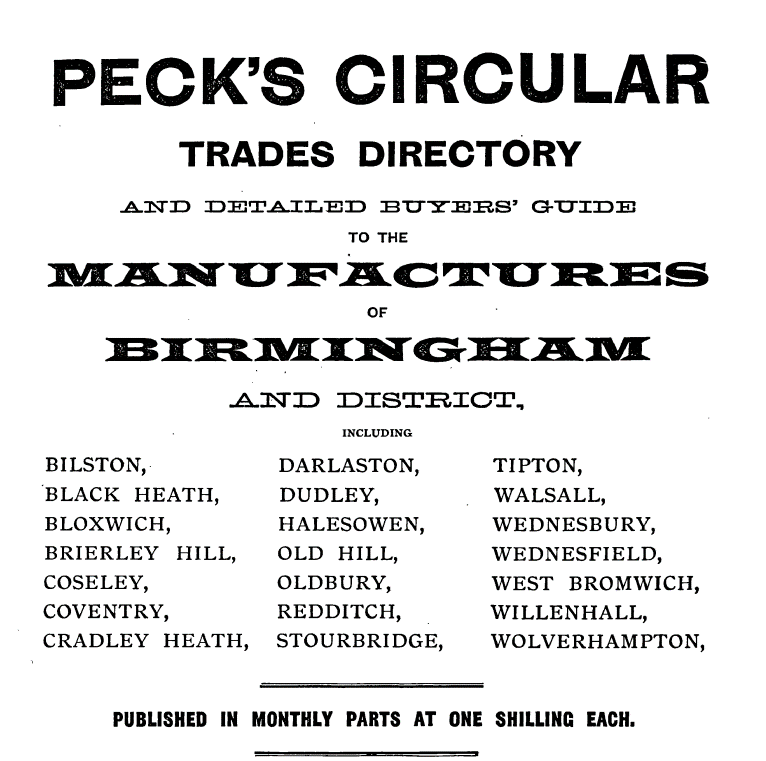

Thanks to the ‘Peck’s Circular Trade’s Directory’ for 1896/97, we find another piece of the puzzle, just not the piece we were expecting.

Thanks to the ‘Peck’s Circular Trade’s Directory’ for 1896/97, we find another piece of the puzzle, just not the piece we were expecting.

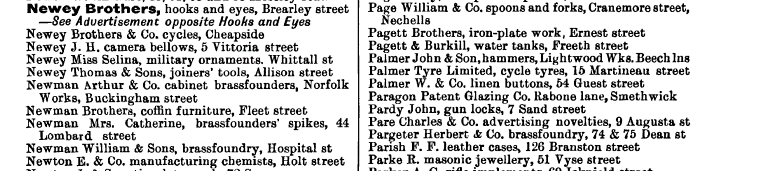

On page 299 in the Birmingham Alphabetical List, we find ‘Newman Arthur & Co. cabinet brass founders, Norfolk Works, Buckingham Street’. It appears that Edwin had gone into business with another of his brothers, this time ‘Arthur’ who was just one year older than Edwin. Surprisingly though, Arthur is listed as a ‘jeweller’ on all census data between 1881 and 1901. By 1911, his occupation has changed, but not to what we were expecting, as he is recorded as a ‘Retail Tobacconist’.

So, it seems that Edwin used the £900 capital share he received after dissolving his partnership with Alfred to set up a new business specialising in cabinet fittings. He went back to what he knew. The odd thing about all of this is that we can’t find mention of him in any trade directory in 1896 or 1897, just his brother Arthur.

Did Edwin go bankrupt before he managed to list his business in the trade directories, leaving his brother Arthur to take over and change its name? Or was the business always in Arthur’s name? We don’t know for sure, but we do know that Edwin was recorded as the main occupier on the Rate Book for 1896. Normally this was usually reserved for the name of the business owner.

Just 16 months after dissolving the partnership with his younger brother Alfred, Edwin had filed for bankruptcy in December 1896. He had liabilities of £697 10s 3d and attributed the insolvency to loss in trade. Although we’ve solved some questions, it opens up a host of others, namely why in his bankruptcy hearing the newspaper report says, “there being no assets”. Had he sold off the plant and machinery to pay some creditors? After all, Edwin had invested almost £900 into the business.

But back to the facts. Arthur Newman & Co. was in business until at least 1901. After that point it seems to disappear from the Rates and Trade Directories. The next indication we have of what the brothers were doing is in 1911 when the next census was published. Edwin is listed as a ‘Hardware metal agent’, Arthur as a tobacconist and Alfred, the youngest of the three, as a ‘Coffin Furniture Manufacturer, Employer’.

Looking at the Rates for 1906, it reveals that the Norfolk Works property Edwin and Arthur were renting on Buckingham Street was empty. Unfortunately there aren’t rates for 1902 to 1905 to determine if any Newmans were still occupying the property during this period.

Whatever the reason for Edwin leaving Newman Brothers, one thing’s for certain. The coffin furniture trade was booming in 1894 and Newman Brothers was a profitable enterprise. We’ll never know for sure, but it would appear that there were disagreements between the two original Newman Brothers, which resulted in Edwin leaving and returning to the ‘original plan’: making cabinet fittings. We know that the ‘Alliance’ were operating at the time, acting as a cartel and artificially controlling business in the coffin and cerement trades, forcing Master Coffin Furniture Manufacturers to join them or face the consequences. I wrote a blog about this back in 2015 (Read it here), so won’t go into the details, but given the drama this caused for Newman Brothers, we’ve often wondered if this was ‘the final nail in the coffin’ for Edwin, convincing him to leave business and return to an area of manufacturing with less jeopardy. Or perhaps the brothers couldn’t reconcile their differences for other reasons.

Part of me never thought we’d get this far in the Edwin Newman saga, so ‘never say never’ as the information is out there, it just has to be found. Who knows what we’ll discover in another 10 years’ time.

Once again, special thanks to Suzanne Hayes for her expert research and for inspiring me to always keep looking! You make the difference and you never give up. Keep doing what you’re doing xxx

Sarah Hayes

Museum & Trust Director