Donna Taylor is a doctoral researcher at the University of Birmingham. She is currently writing a thesis on the origins of Birmingham Town Council and is owner of the blog ‘Notes from Nineteenth-Century Birmingham’.

On July 19th 1881 Mayor Richard Chamberlain laid the foundation stone of Birmingham’s first municipal art gallery and museum. It was a significant moment in the town’s cultural history, the result of decades of petitioning and planning by the local community. Civic pride was at the heart of the campaign, a desire to show off all that the town had achieved in a relatively short space of time. Less than a century before the laying of the foundation stone Birmingham’s first historian, William Hutton, had penned a bleak description of narrow, muddy streets ‘puddled with stagnant water’. In Hutton’s time the products that came from Birmingham also had a poor reputation, with ‘Brummagem ware’ often used as a byword for badly made, cheap and flashy items. By the later nineteenth century all of this had changed and ‘the city of a thousand trades’ had gained an important place at the economic heart of the British Empire. It had become widely acknowledged that if an item was not made in Birmingham, then it was not made anywhere. The inscription on the foundation stone reads ‘By the gains of industry we promote Art’. In this succinct statement Birmingham presented itself as not only a giant of industrial innovation, but also as a national cultural leader.

In 1856 Charles Adderley donated 8 acres of his family’s ancestral home to the council and this became Birmingham’s first public park, free to use by everyone. There was also an intention to build a fully accessible museum and free library as part of this project. In April 1856, Aris’s Gazette advertised a fund raising sale of ‘fancy goods’ to support the project which, the article expressed, ‘is one that every reflecting person who has watched the rapid increase of this town, and has taken the slightest interest in the welfare of its immense population, must have long considered of the highest importance’. The promotion of a public museum was not only of economic importance, but had a social significance, the dissemination of knowledge and culture to the whole community. It was a paternalistic approach, one which is so often associated with the Victorian period, but it was also a groundbreaking one, pushing aside notions that cultural pursuits were only for the privileged and wealthy minority. At the same there was a drive for greater accessibility to education; in 1845 an adult education school was opened at Severn Street and in 1854 the Birmingham Midland Institute (BMI) was founded by act of parliament ‘for the diffusion of and advancement of science, literature and art amongst all classes of persons resident in Birmingham and the Midland Counties’. This latter was famously supported by Charles Dickens, who visited the Town Hall in 1853 to give personal readings of ‘A Christmas Carol’. The first reading was to a paying audience of around 2000, for the purpose of raising funds for the BMI. But he also did another, free reading, at the Town Hall for the working men and women of the town. Birmingham’s cultural advance was clearly not just an issue of local importance, but attracted a much wider interest, a demonstration of the rapid changes taking place in the town.

In 1870 the resident artisan glass makers of Birmingham presented a memorial (a sort of letter of request) to the council ‘announcing that they had associated themselves into a working committee for the purpose of founding an Industrial Museum…after describing the advantages of industrial museums to large towns like Birmingham, the memorialists concluded by suggesting that the Council might reasonably take into consideration the granting of a sum of money for establishing a central Indu strial Museum for the town and district generally’(Aris’s, April 9th, 1870). The request was forwarded to the council’s Free Libraries Committee and it seems something of a ball was finally put into motion. The spending of ratepayers money had (and of course remains) a point of tension in the town. The council, which was founded in 1838, after a period of capital spending on the building of a prison and asylum in Winson Green and the public baths at Kent Street, been faced with extreme and well organised opposition to any further large projects. Nevertheless, at the time that the artisan glassmakers made their request, Birmingham had managed to open three public parks, a Central Library and three branch libraries. These were largely the result of individual effort and philanthropy and, of course, the indomitable, petitioning spirit that has defined modern Birmingham. But it would take the brilliant planning of Joseph Chamberlain’s council to finally enable investment in a public, municipal museum.

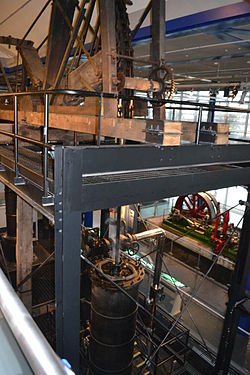

In 1874, Joseph Chamberlain, then Mayor of Birmingham, led the council to apply for an Act of Parliament which would allow them to purchase all of the private gas companies in the town. This was granted and the Birmingham Corporation Gas Company was established. Profits from the company, now owned by the Birmingham ratepayers, would be ploughed back into a municipal museum. An opulent payment office was built as an extension to the Council House, where people could go and pay their gas bill and also see exactly where their money was being spent. The payment office is now called the Waterhall and is one of the museum’s many exhibition galleries. This was such a clever move by Chamberlain: the museum was still the property of the people and businesses of Birmingham, who were funding it through their gas bills. But it also avoided antagonising the ratepayer protection lobby. It also marked the emergence of what was known as Municipal Socialism, led by Chamberlain and which led to Birmingham being described in 1890 as ‘the best governed city in the world’ by a journalist writing for the American Harper’s magazine.

Our museums are an integral part of the proud and inspirational history of Birmingham. Today we are spoilt for choice in the number of heritage sites and art galleries that we have on our doorstep. Amongst these are nine which are currently at a real risk of being lost to the public, along with all the great industrial artefacts which inspired our early city fathers to pursue the establishment of municipal museums. It is easy enough to pass by the Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery and think ‘I must pop in there one day’, or to maybe to go in for a mooch without actually being fully aware of what it actually reveals about our city’s incredible history. The introduction of public access to culture was part of a radical movement that helped to shape modern Britain, and Birmingham played a vital role in this change. I have written this post because I have a personal passion for and pride in my city and want to ensure that all of its heritage is preserved for future generations. Thousands of school children benefit from visits to the museums and they also offer other important social opportunities, such as the innovative Birmingham Museum’s Health and Wellbeing project which has established a Dementia Cafe at Soho House and a garden project at Sarehole Mill for people with mental health conditions.

The recent announcement of city council cuts across the cultural sector will have a hugely negative impact but it is especially important to preserve our heritage, because once it is gone, it will be gone forever. This is not in the spirit of the Birmingham tradition of innovation and accessibility. It would be wonderful to see a revival of Chamberlain’s Municipal Socialism, but for now I would urge everyone to voice a protest against the Council’s cuts to OUR heritage.

Please sign the online petition here:

And please keep supporting our museums. Ta.