The stage was set for the arrival of the coffin furniture trade in Birmingham as early as the first quarter of the eighteenth century, when the leather and textile trades which had dominated Birmingham’s early industrial history gave way to the metalworking industry.

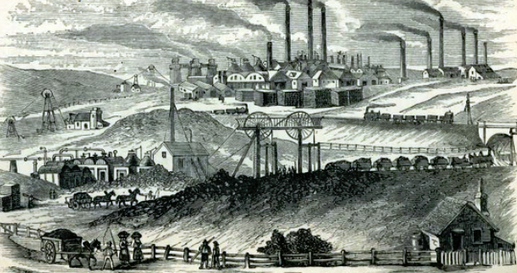

The rapid growth of coal mining and iron manufacturing in South Staffordshire in the period meant that raw materials were readily available to enterprising craftsmen searching for new industries. The low raw material transport costs, combined with the growing skill of local craftsmen allowed for big profit margins and led to the rapid expansion of Birmingham’s metalworking trade in the late eighteenth century. A prosperous industrial environment emerged, in which skilled workers were able to leave their masters and set up their own businesses. The city emerged as a hub for skilled craftsmen and small, specialised factories.

The area now known as the Jewellery Quarter became a popular location for these trades; a lack of restrictions on the building of small workshops in the gardens of houses on the Newhall Estate meant that small businesses could be set up with little capital outlay. The concentration of trade in the area was further consolidated by increasing specialisation and sub-division of process in the metalworking industries, which forced the localisation of increasingly inter-connected businesses. By the mid-nineteenth century, the area had become a dense and vibrant industrial village in the heart of the city in which masters, workers and their families both lived and worked.

The area’s main industry was obviously the manufacture of jewellery, though this was by no means the Quarter’s only trade, as the skills and processes required to make jewellery were applicable to many other metalworking industries. The coffin furniture trade itself had arrived in the area as early as 1760, when enterprising Birmingham tradesmen began to compete with the Southwark firms who had previously dominated the industry. They offered cheaper prices and an ability to adapt to new technologies and changing consumer demands; the 1769 invention of Pickering’s stamp press made mass-production easier, whilst the emergence of dies at the end of the eighteenth century brought further simplification and savings in cost of up to 80%. The perfection of die-sinking in the early 1800s improved the quality and variety of designs, essential to compete in the massively regionally and socially variable coffin furniture market. The Jewellery Quarter became known as a source of high quality goods; its matte black “japanned” coffin fittings (silver dipped tin painted with a thick black lacquer) were the height of fashion for upper class Victorian funerals.

By the mid 19th century, the Jewellery Quarter had become the centre of Britain’s coffin furniture trade, which employed around 200-300 local workers. Demand for coffin furniture rose in the third quarter of the century, when the death rate began to reflect the massive population explosion of the late eighteenth century. Companies would consume around 40 tonnes of iron per year, with the area as a whole consuming 60-80 tonnes of block tin annually. The industry was hugely successful, as the nature of the products meant that there was little to no fluctuation in demand across the years.

The rapid growth of coal mining and iron manufacturing in South Staffordshire in the period meant that raw materials were readily available to enterprising craftsmen searching for new industries. The low raw material transport costs, combined with the growing skill of local craftsmen allowed for big profit margins and led to the rapid expansion of Birmingham’s metalworking trade in the late eighteenth century. A prosperous industrial environment emerged, in which skilled workers were able to leave their masters and set up their own businesses. The city emerged as a hub for skilled craftsmen and small, specialised factories.

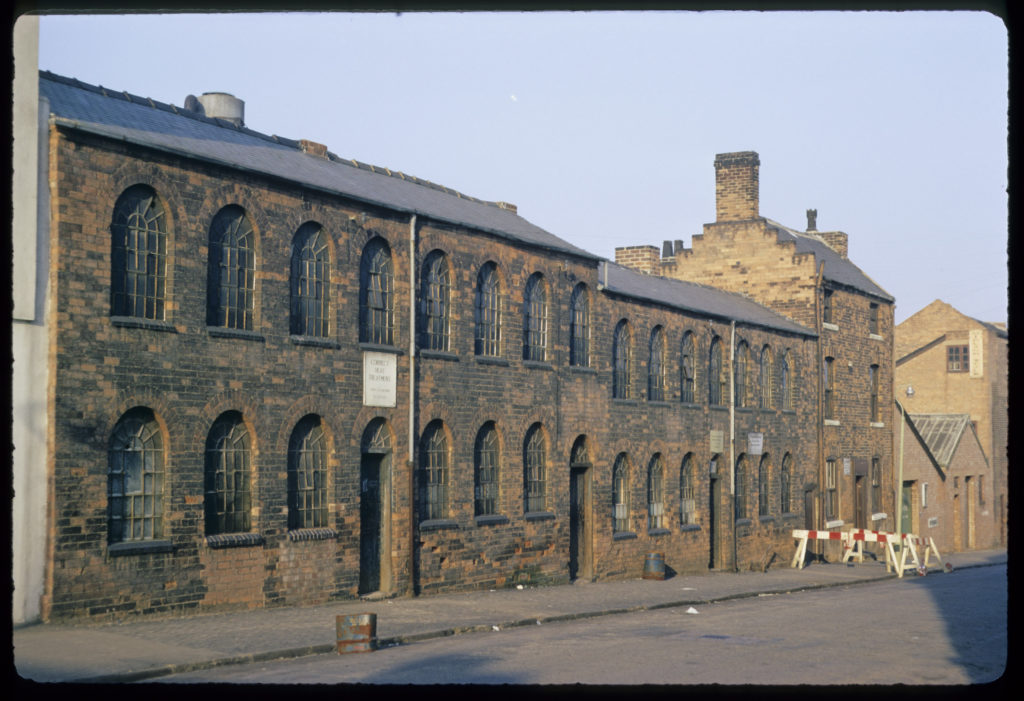

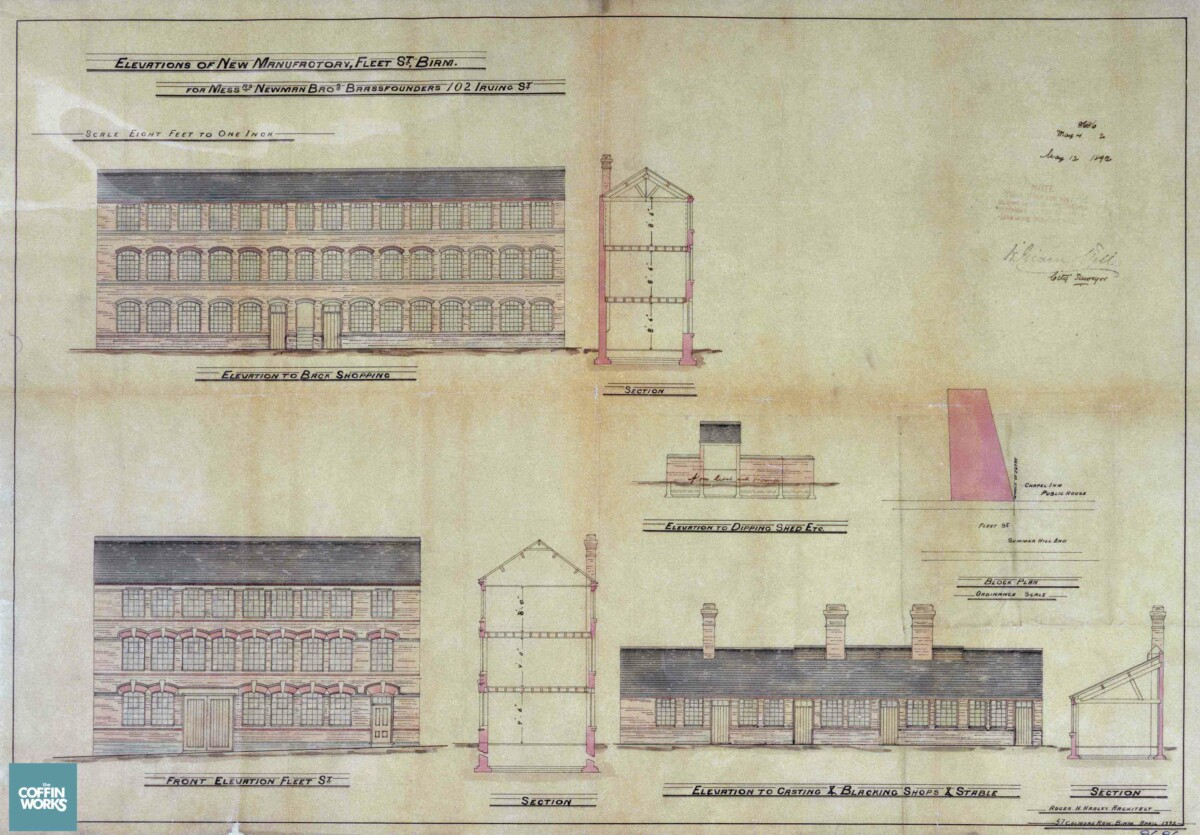

The original Newman Brothers, Alfred and Edwin Newman, arrived at the industry’s peak, having begun as brass founders in 1882. They originally operated from premises in the Eastside area of the city. As brass founders, their business was based on casting an assortment of metal articles, in this case, largely cabinet furniture from molten brass. In 1894 the company moved to new premises at 13-15 Fleet Street in the Jewellery Quarter and began to specialise in coffin furniture of the highest quality.

The Jewellery Quarter as a whole continued to grow in the twentieth century, by 1914 jewellery and its related trades (including the manufacture of coffin furniture) employed more than fifty thousand people in the area.

Miles Dabbs, Volunteer