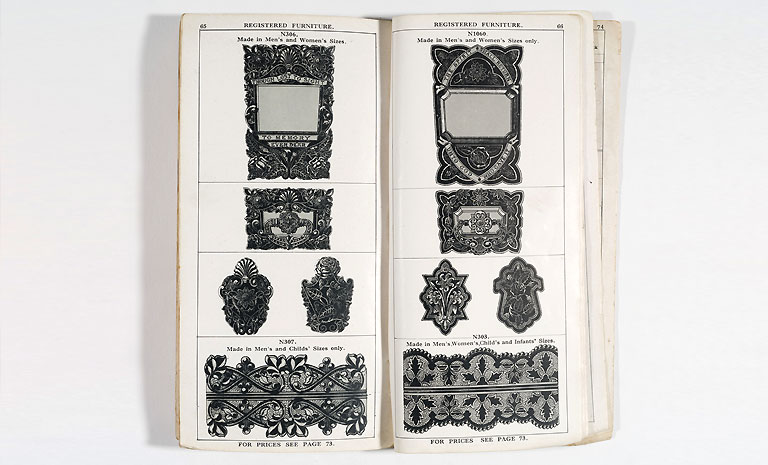

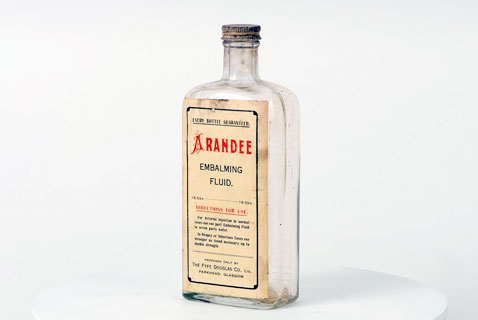

The area’s main industry was obviously the manufacture of jewellery, though this was by no means the quarter’s only trade, as the skills and processes required to make jewellery were applicable to many other metalworking industries. The coffin furniture trade itself had arrived in the area as early as 1760, when enterprising Birmingham tradesmen began to compete with the Southwark firms who had previously dominated the industry. They offered cheaper prices and an ability to adapt to new technologies and changing consumer demands; the 1769 invention of Pickering’s stamp press made mass-production easier, whilst the emergence of dies at the end of the eighteenth century brought further simplification and savings in cost of up to 80%.

360° View of a Die block

Use the play button to rotate the object automatically, or alternatively you can drag the item with the mouse or your finger to move it around.

The perfection of die-sinking in the early 1800s improved the quality and variety of designs, essential to compete in the massively regionally and socially variable coffin furniture market. The Jewellery Quarter became known as a source of high quality goods; its matte black “japanned” coffin fittings (silver dipped tin painted with a thick black lacquer) were the height of fashion for upper class Victorian funerals.

By the early to mid-19th century, the Jewellery Quarter had become the centre of Britain’s coffin furniture trade, which employed around 200-300 local workers. Demand for coffin furniture rose in the third quarter of the century, when the death rate began to reflect the massive population explosion of the late eighteenth century. Companies would consume around 40 tonnes of iron per year, with the area as a whole consuming 60-80 tonnes of block tin annually. The industry was hugely successful, as the nature of the products meant that there was little to no fluctuation in demand across the years.