Origins of the Business

Newman Brothers was established in 1882 by Alfred and Edwin Newman. They began business as brass founders who specialised in cabinet fittings and worked from rented factories in Birmingham. In 1892 they commissioned architect Roger Harley to design a manufactory in the Jewellery Quarter to be dedicated solely to the production of coffin furniture, that is the handles, crucifixes and ornaments that adorn the outside of coffins. Two years later they moved into these new premises on Fleet Street, which they called the Fleet Works but is today known as the Coffin Works.

In 1895, only a year after the factory had opened, the partnership between Alfred and Edwin Newman was dissolved and Alfred went on to run the business as a sole trader.

The Newman Brothers’ Factory: a Special Place

When Newman Brothers’ Coffin Works in Birmingham’s Jewellery Quarter was built in 1894 Queen Victoria was still on the throne and when it finally closed its doors it was 1998.

This place is special for three reasons:

First, when the factory closed, almost everything in it was left untouched, the machinery, the stock, there was even a pot of tea on the stove. It has been described as a sort of mercantile Marie Celeste.

Second, it made a rather unusual product: coffin fittings. These are the handles, breastplates, screws and ornaments for a coffin. They also made the ‘soft goods’ for a coffin: the linings, frills and cushions, as well as the funerary gowns for the deceased. In fact, they made everything for the coffin except the coffin itself. They sold directly to undertakers and funeral directors, not the general public.

The third reason the factory is special is that Newman Brothers didn’t just make coffin fittings, they made the very best coffin fittings. The royal undertakers were among their customers and Newman Brothers’ coffin fittings have adorned the coffins of George V and VI, Queen Mary, Princess Diana and the Queen Mother, as well as great statesmen such as Winston Churchill.

Learn more about the royal connection by clicking here.

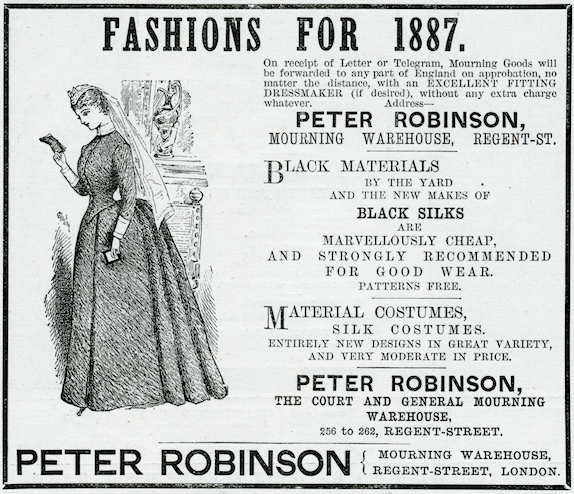

Over the factory’s one hundred years in business society changed a great deal as did attitudes to death and funerals. Newman Brothers represents the high point of fashion for lavish funerals, and as attitudes changed their business declined particularly after the Second World War. The factory is so old-fashioned that some of the machinery is still original, having never been updated. Almost everything else was very out of date by the time the factory closed.

The last proprietor, Joyce Green, who had worked at the factory for 50 years, realised what a special place this factory was, and was determined to preserve it as a museum. Heritage organisations agreed, and although it took 15 years, in 2014 Birmingham Conservation Trust was proud to re-open the factory as a heritage attraction. Unfortunately, Joyce did not live to see that day.

Alfred Newman died In 1933. He may have known that he was terminally ill because this was the year he decided to incorporated the company which became Newman Brothers (B’ham) Limited. The company was valued at £12,500 (about £786,000 in today’s terms). On Alfred’s death, the shares were divided equally between his two sons Horace and George, his daughter Nina, and his grandchildren. Horace and George took over the running of the business together. George died in 1944 and Horace in 1951. After this the business went on to be managed by a number of shareholder directors none of who were Newman family members.

RESCUE AND RESTORATION: The Rescue Mission

In 1999 the firm of Newman Brothers (B’ham) Limited was finally wound up. More than a hundred years of history seemed to be at an end. The likely fate of the dilapidated old factory was demolition. Newman Brothers’ factory has survived due to the combined efforts of the final proprietor Joyce Green, the many organisations and individuals who also recognised its importance for the history and heritage of Birmingham and the nation.

In 1998-99 English Heritage was undertaking a major survey of the manufactories of Birmingham’s Jewellery Quarter and they ‘discovered’ the Newman Brothers’ building just as the factory was in the process of winding down. English Heritage recognised its importance immediately, and had it listed at Grade II* in 2000, which protects it from demolition.

Birmingham Conservation Trust (BCT) first became involved in the Coffin Works in 2001, when a report was commissioned to look into what options there were for the future of the building. The report concluded that turning the whole factory into a museum was unlikely to generate sufficient income to maintain the building. The BCT therefore recommended a mixed use idea wherein half of the factory would become a museum attempting to preserve the rooms as they looked when the business closed; the other half of the building would be converted into units for let. This would generate two separate income streams to ensure a sustainable future.

In 2002 BCT submitted a bid to Advantage West Midlands (AWM), a regional development agency, for AWM to purchase the building and its contents on the understanding that the Trust would undertake the restoration work. This turned into a nail-biting experience for the Trust as AWM only completed the £400,000 purchase in the final hours of the financial year, on the 31st March 2003.

Left to right: Bob Beauchamp, BCT chair, Elizabeth Perkins, former BCT director, Simon Buteux, current BCT director, Suzanne Carter, tireless Development Manager of BCT, and Cllr, Peter Douglas Osborn.

Now there ‘just’ remained the task of raising the funds for the repair and conservation of the Coffin Works. In the vanguard was BCT’s dynamic Director, Elizabeth Perkins, who was at the time heavily engaged in the restoration of the Birmingham Back-to-Backs and negotiating their transfer to the National Trust on completion. The first series of the BBC’s Restoration programme, hosted by Griff Rhys Jones, offered an early publicity and fund raising opportunity.

The excitement mounted in August 2003, when the Coffin Works was one of program’s three nominees in the English Midlands, but we didn’t make it to the finals. That year Victoria Baths in Manchester went away the £3.4 million prize money. Nevertheless, the programme had raised the profile of the Coffin Works, and it was featured again by the BBC in Radio 4’s Hidden Treasures, presented by Lucinda Lampton, in July 2004.

However, problems had begun to emerge. Surveys had established that the Coffin Works was badly contaminated and was also riddled with asbestos. Advantage West Midlands put the project on hold while the problems were dealt with. As months turned into years, the overall condition of the building was deteriorating too.

Despite emergency repairs, the state of the roof was getting worse, and water was pouring in, collecting in buckets which BCT staff and volunteers had to empty every time it rained. This was putting the building’s contents at risk, especially the more fragile items such as the paperwork in the Office and the fabrics in the Shroud Room. In 2007 The decision was made to move the factory’s contents off site for safe storage, everything except the heaviest machinery. But not before it was all carefully photographed in situ and catalogued, so that one day things could be returned to their former places. All this involved more trouble and expense.

There was one other very important piece of recording needed to be done – before we moved the stock we had to record the stories of former factory workers for posterity while they were still alive and their memories fresh.

There was one other very important piece of recording needed to be done – before we moved the stock we had to record the stories of former factory workers for posterity while they were still alive and their memories fresh.

In 2006 we interviewed the final proprietor Joyce Green, and as many of the employees as possible, on camera in their old workplace, which brought the memories flooding back.

Meanwhile, Elizabeth Perkins and her colleagues at Birmingham Conservation Trust were also working on the research and paperwork needed for major grant applications. Initial applications to Advantage West Midlands and the Heritage Lottery Fund had been turned down, plans had been altered, and hopes were dashed again.

But by March 2009, everything looked set fair for the project to get the funding it so desperately needed, with revised applications submitted to both Advantage West Midlands and the Heritage Lottery Fund.

Then disaster struck. In the wake of the 2008 recession, the government cut almost all funding to the regional development agencies, and AWM had to withdraw its funding offer to the Coffin Works. It was back to the drawing board. Historic building conservation is not for the faint hearted.

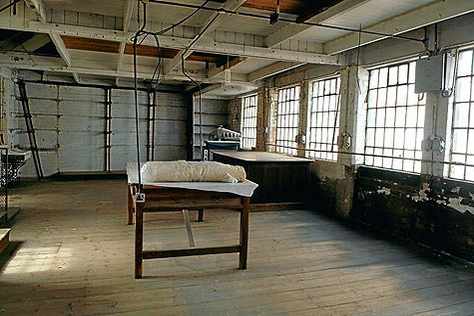

The whole building was in need of desperate attention. The Plating Shop, shown here, had to be decontaminated due to the dangerous chemicals used in there over many years. In the end, everything had to be removed from the Plating Shop because of contamination. Today it forms part of our let office space.

Without funding from Advantage West Midlands and in the climate of post-recession austerity, plans for the Coffin Works had to be scaled down. Fortunately, in the process of winding down, AWM agreed to sell the Coffin Works and its contents to Birmingham Conservation Trust for a ‘knock-down’ price.

Birmingham City Council provided a grant of £150,000, which made the purchase possible. By August 2010 the Trust was proud owner of the Coffin Works, albeit in a derelict state. English Heritage put their money where their mouth was, eventually contributing £450,000 for repairs. This helped to take the Coffin Works off the Buildings at Risk register.

By June 2011 the Heritage Lottery Fund had approved a grant of £999,400. Things were going in the right direction at last, although it wouldn’t be until 2013 that all the funding needed for the almost £2 million project had been put in place that work could start on the restoration. It had taken 14 years.

Sadly, Joyce Green, Newman Brothers’ last managing director, without whom the rescue would never have happened, did not live to see the happy day. Joyce had died in 2009.

Elizabeth Perkins the Director of Birmingham Conservation Trust never gave up on the project through the highs and lows of the struggle to raise the funds. in 2012 Elizabeth moved on to a new job, leaving a new Director, Simon Buteux, to oversee the ‘easy bit’, the restoration work itself.